Remembering U.S Navy’s First Black Officers During Black History Month 2024

Black History Month grew from the ‘Negro History Week’, a brainchild of American Historian Carter G. Woodson and famous African Americans. Every U.S. president has officially designated February as Black History Month since 1976 to raise awareness about the role of African Americans in the country’s history.

African Americans have played a significant role in making the U.S. what it is today. They have been an active part of the U.S. Armed Forces, and this Black History Month, we remember the efforts, commendable service and accomplishments of the U.S. Navy’s First Black Officers who paved the way for future generations.

Training U.S. Navy’s First Black Officers- The Backdrop

The decision to train Black Naval Officers resulted from a 4-year campaign which started along with the war preparations. In 1940, President Franklin D Roosevelt called upon the United States to become an arsenal of democracy and to defend democratic ideals.

Civil rights leaders and activists questioned how the U.S. could preach these ideals when discrimination existed in its own Navy. Hence, from 1940 to 1944, thousands of African Americans beseeched congressmen to let Black men serve equally in the U.S. Navy.

From 1893 onwards, African Americans were only allowed to work as Messman or Culinary Specialists and Retail Service Specialists or Steward jobs, which segregated them from the Navy community. They could not become commissioned officers.

Though the first black officer of the Army graduated in 1877 from West Point and by the Second World War, the Army had a black General; the Navy suspended the enlistment of Blacks from 1919 to 1933.

A month after the Pearl Harbour attack, the Navy’s General Board met in Washington and discussed training African Americans for general service ratings. In the 18 months that followed, thousands of African Americans were trained to become quartermasters, machinists and electricians.

Though some barriers were removed, a significant one remained. By the end of 1943, there were still no Black Navy Officers, given there were 60,000 black men in the Navy, and 12,000 more were entering every month.

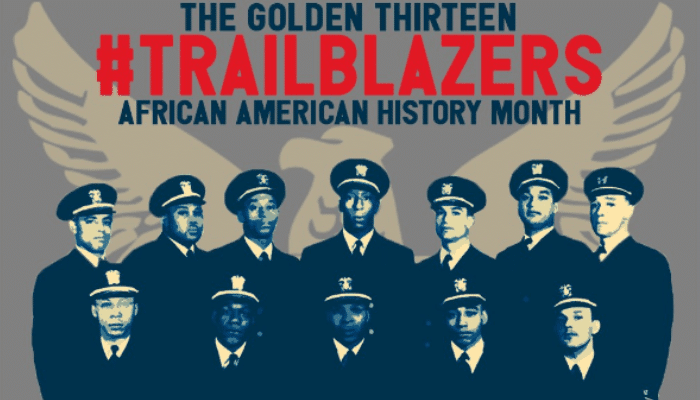

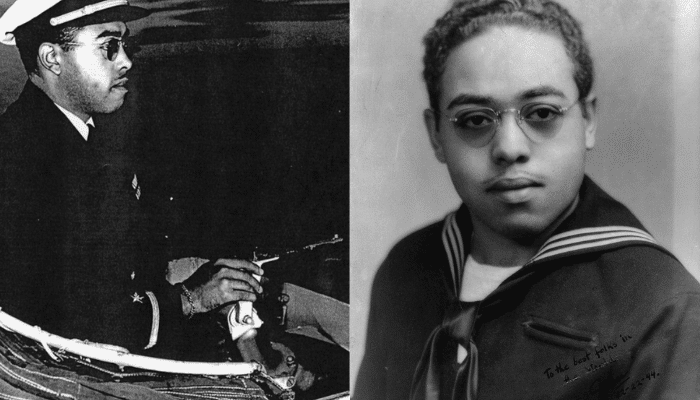

The First Black Navy Officers- ‘The Golden Thirteen’ & Their Legacy

As political pressure increased, 16 black candidates were picked from the ranks to undergo officer training at Great Lakes Naval Training Station in Illinois under the guidance of white officers.

Their journey was surely not an easy one. There were thousands of blacks in the Navy, and if any were ever to adorn an officer’s uniform, command a naval ship or lead white men into battle, then these 16 men had to succeed.

These 16 men, who were the children and grandchildren of slaves who had seen their family members getting physically and emotionally abused or denied employment and equality because of their skin colour, had to prove that blacks could command and lead and that they had all the qualities to wear the gold stripes.

Sam Barnes, one of the 16 men, recounted that many hoped they would fail, but they did their best despite the great responsibility placed upon them. There was plenty of equipment which could aid their training, but they could not use any of it.

They trained separately from other sailors, drilled and ate alone and even lived in their own barracks in a segregated section of the station. Hence, equal opportunity did not mean equal treatment. In later interviews, they recounted how some of their instructors were not interested in whether they learned anything at all.

However, this made them work even harder. Though supposed to be in bed by 10:30 p.m., they sat together in the bathroom with flashlights, revising the day’s lessons and preparing for the coming lessons. They covered the windows with sheets so nobody would see the light coming from the room.

Despite the 20-hour days, the racism and the ridicule they were subjected to, they maintained their calm. They were aware that losing their temper could fuel the prevalent idea that black men didn’t possess the demeanour required for command.

As the training neared completion in March 1944, they scored grades, unlike no other officer class in history. Their marks were so good that many in Washington could not believe it, and they were forced to take the exams again, scoring even higher the second time, earning a collective 3.89 out of 4.0 for the entire course.

They all passed, but only 13 received commissions, 12 as ensigns and 1 as a warrant officer and no official explanation was given for this decision. Hence, though this group scored higher than any other class, they had the same pass rate as an average class of white officer candidates.

These first black officers were involved in running drills, giving lectures on venereal diseases, and patrolling waters off the California coast. Combat was out of the question, and though they were ignored, they kept their heads high. One was William Sylvester White, who recalled, “We were the forerunners. What we did or did not do determined whether the program expanded or failed.”

Two months later, the Navy commissioned 10 more men, and they proved just as capable as the first 13. However, the achievements and hard work of the first 16 men were never appreciated, and for a long time, they were referred to as ‘those black naval officers.’

By the end of the 1970s, the Navy finally recognised them as a symbol of racial integration, progress and pride. Their first reunion was in Berkeley, California, in 1977, where Captain Edward Sechrest, a Vietnam veteran, coined the term “Golden Thirteen”.

On this occasion, the men came face to face with their legacy. They had never seen dozens of black officers in the same room before, and now they were being greeted by black lieutenants, captains and even an admiral who thanked them for their hard work and sacrifice.

Among these 13 men was Charles Byrd Lear, the only one appointed as a warrant officer and who became the first African American Chief Warrant Officer.

Though not a part of the Golden Thirteen, Vice Adm.Samuel L. Gravely Jr was the first African American to be commissioned through the U.S. Navy’s V-12 Program, the predecessor of today’s Naval Reserve Officer Training Corps.

He enlisted in 1942 and entered the program after the boot camp at Great Lakes. His 36-year career represents many firsts for African Americans.

Gravely was the first African American to serve on a fighting ship as an officer, the first to command a Naval Ship, the first fleet commander and the first to become a flag officer, finally retiring as a Vice Admiral.

He served on the USS PC-1264, a World War II Navy Ship with predominantly Black Crew Members. He was the communications officer on the battleship USS Iowa during the Korean War, and in 1961, he commanded the destroyer USS Theodore E. Chandler. He retired in 1980, and in 2010, the Arleigh Burke Class Guided Missile Destroyer USS Gravely was named after him.

John W. Lee Jr. was the first Black commissioned Navy officer who achieved this historic feat in 1947. His personal mission was to help other Black servicemen get the same opportunities that he did.

He was born in 1924 and entered the Navy in 1944. After he left the boot camp, he was admitted into the V-12 Officer Candidate Program at Indianapolis’ DePauw University and graduated as an Ensign.

He also served in the Korean War and was assistant navigator for the USS Kearsarge. He was a part of many war and support missions onboard the USS Toledo and USS Wright. Lee became the commanding officer of the Oceanographic Detachment Two division in 1960. He became the Lieutenant Commander before his retirement in 1966. He died at the age of 85 in 2009.

Alfred Masters was the first African American Marine. He was enlisted in the USMC in 1941 in Oklahoma City. His first training camp was at Montford Point in North Carolina.

As part of the 52nd Defense Battalion, he was deployed to Majuro in the Marshall Island Group and Guam in the Marianas. By 1944, he became a Technical Sergeant in the Commissary Branch. His fellow marines said he was stern but fair and knew how to lead. After his return to the States, he was discharged in 1945 and returned to his family.

In his later years, he taught agriculture, worked in labour-intensive occupations, and returned to farming his own land in Vado, New Mexico. He fought for his rights and those of others around him. He died in 1975.

Born in 1936, William Goines became the first African American Navy SEAL. He enlisted in the Navy in 1955, and in 1957, he was one of the 13 men who completed the training. When John F. Kennedy created the first 2 SEAL teams in 1962, he was among the 40 men chosen to join the second team. He served three tours in the Vietnam War and even led a Vietnamese unit once. He retired in 1987 as a Master Chief Petty Officer after 32 years of commendable service.

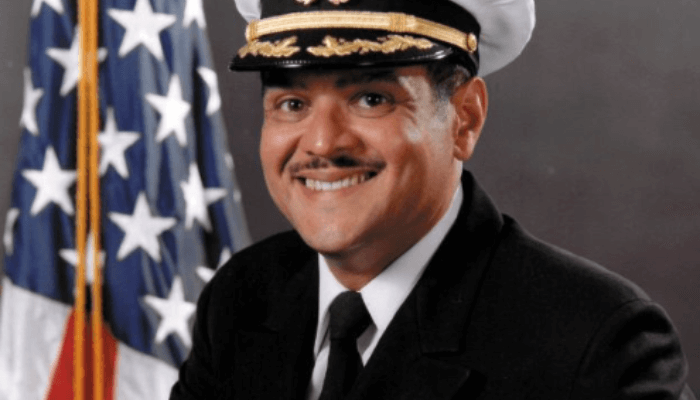

On 28th May 1983, Pete Tzomes became the first African American to command a nuclear-powered submarine, the USS Houston. He was followed by six others, and the designation of Centennial Seven recognised their accomplishments as they were the first African Americans to command submarines in the first 100 years of submarine service.

Born in 1944, Tzomes wanted to be a Marine Corps Pilot, but he was short, so he decided to pursue a career in the submarine force. He graduated in 1967 and received his commission as an ensign. He was a part of many shore tours and was honoured with many awards, such as the 1991 Black Engineer of the Year Award, for his efforts to lead the Navy’s equal opportunity programs into the 21st century.

Wesley Anthony Brown was the first African American to graduate from the US Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, in 1949. He was nominated for admission and appointed to the Academy by New York Congressman Adam Clayton Powell Jr.

He retired as a lieutenant Commander in 1969 after 20 years of service in the Navy’s Civil Engineer Corps, where he was engaged in building homes for military service members in Hawaii, wharves in the Philippines, roads in Liberia, a desalination plant in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba and a nuclear power plant in Antarctica.

He was bestowed with the American Theater Ribbon and World War II Victory Medal and recognised with the 2009 National Society of Black Engineers Golden Torch Legacy Award-First Honoree.

The First Black Women Naval Officers

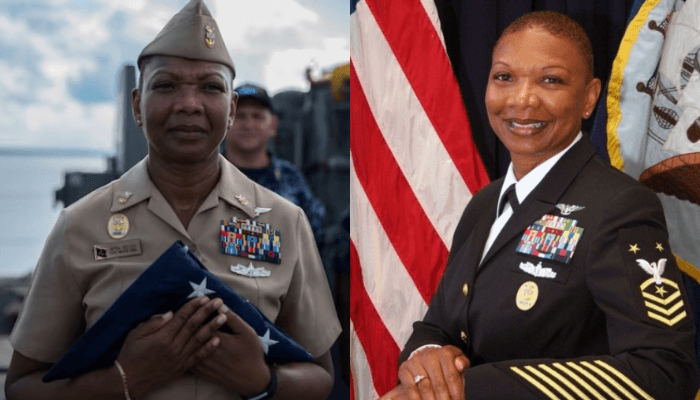

Women also made tremendous contributions to the Armed Forces. Michelle Howard, born in 1960, became the first African American Woman to captain a Navy Ship, the USS Rushmore, in 1999.

She entered the U.S Naval Academy, Annapolis, Maryland, in 1978 and became one of the seven Black women in the class of 1363 students. After graduating in 1982, she served onboard the submarine tender USS Hunley till 1985. She was also the first lieutenant aboard the USS Flint and served as the executive officer of the USS Tortuga.

April D. Beldo, born in 1964, was the first woman and the first African American in several Navy positions, including the first female Commander Master Chief of the aircraft carrier USS Carl Vison in 2009 and the first female Command Master Chief for recruit training.

From 2012-13, she was the Force Master Chief for Naval Education and Training Command. In 2013, she became the Fleet Master Chief for Manpower, Personnel, Training and Education until her retirement in 2017.

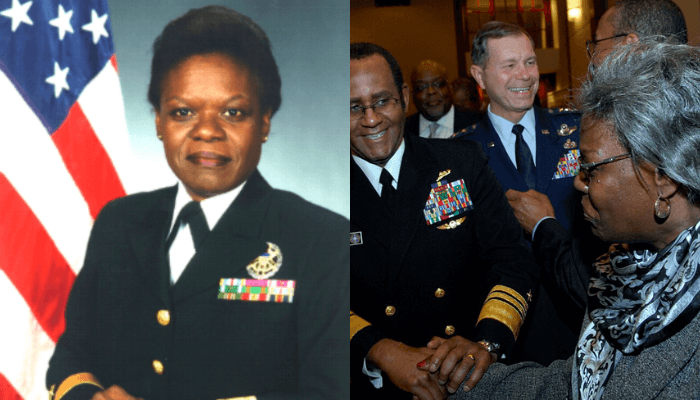

Lillian Elaine Fishburne, born in 1949, was the first African American woman to become a Rear Admiral in the U.S. Navy. She was appointed by President Bill Clinton and promoted in 1998. She retired in 2001.

The firsts still continue. In February 2023, Captain Janet Days became the first Black Woman to take command of the world’s largest naval base by becoming the 51st commanding officer of Naval Station Norfolk. The 6,200-acre installation is home to 63 ships, 188 aircraft, and over 67,000 personnel.

Today, African Americans constitute around 13% of the U.S. population, and only 8.1 % of Naval Officers are black, per a 2019 report by Congressional Research Service.

Conclusion

In this article, we reflected on the journey of the U.S. Navy’s first black officers, who paved the way for future generations despite facing discrimination and racism. They were brave people who served the nation with dignity and distinction.

The Golden Thirteen took courageous steps and broke down racial barriers that had long barred black Americans from attaining leadership positions in the U.S. Navy.

The world has come a long way since then. However, it is important to remember the sacrifices of these trailblazers who made immense contributions to the Armed Forces and did not accept the status quo.

So, this Black History Month, we remember all the black officers who fought for their rights. Their legacy tells us what men can achieve when they stand up against injustice.

You might also like to read-

- 10 Smallest Aircraft Carriers in the World

- 8 Major U.S East Coast Ports

- 10 Major Indian Navy Vessels

- 10 Major Ports Of Greece

- 10 Titanic Captain Facts You Might Not Know

Disclaimer :

The information contained in this website is for general information purposes only. While we endeavour to keep the information up to date and correct, we make no representations or warranties of any kind, express or implied, about the completeness, accuracy, reliability, suitability or availability with respect to the website or the information, products, services, or related graphics contained on the website for any purpose. Any reliance you place on such information is therefore strictly at your own risk.

In no event will we be liable for any loss or damage including without limitation, indirect or consequential loss or damage, or any loss or damage whatsoever arising from loss of data or profits arising out of, or in connection with, the use of this website.

Do you have info to share with us ? Suggest a correction

Disclaimer :

The information contained in this website is for general information purposes only. While we endeavour to keep the information up to date and correct, we make no representations or warranties of any kind, express or implied, about the completeness, accuracy, reliability, suitability or availability with respect to the website or the information, products, services, or related graphics contained on the website for any purpose. Any reliance you place on such information is therefore strictly at your own risk.

In no event will we be liable for any loss or damage including without limitation, indirect or consequential loss or damage, or any loss or damage whatsoever arising from loss of data or profits arising out of, or in connection with, the use of this website.

About Author

Zahra is an alumna of Miranda House, University of Delhi. She is an avid writer, possessing immaculate research and editing skills. Author of several academic papers, she has also worked as a freelance writer, producing many technical, creative and marketing pieces. A true aesthete at heart, she loves books a little more than anything else.

Latest Maritime Knowledge Articles You Would Like:

Subscribe To Our Newsletters

By subscribing, you agree to our Privacy Policy and may receive occasional deal communications; you can unsubscribe anytime.