Real Life Incident: Passenger Ship Strikes Pier Causing Damage Worth $2.1 Million

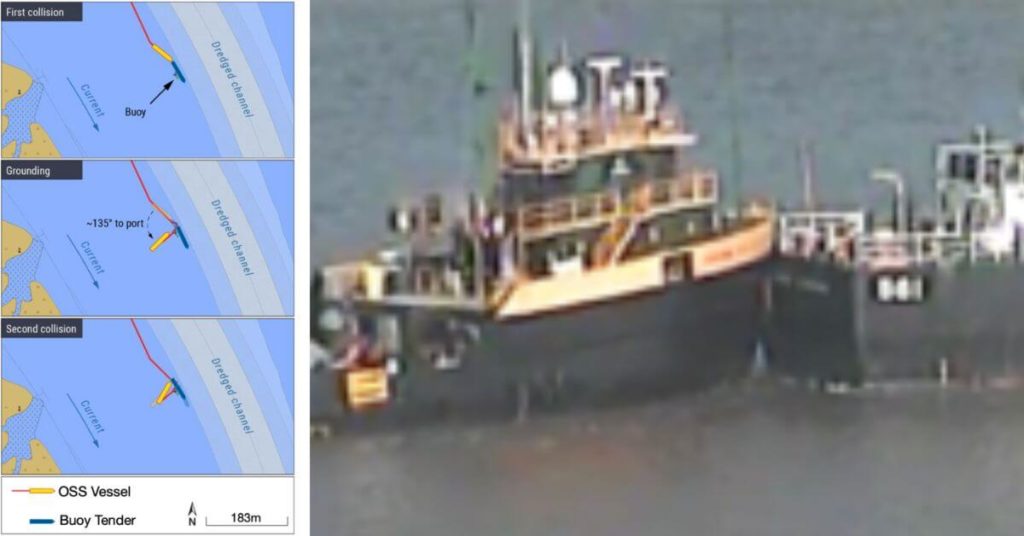

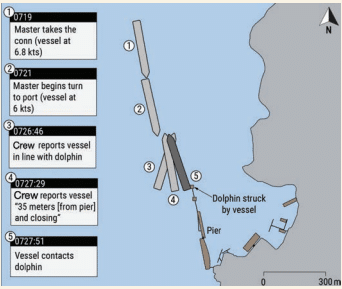

A passenger ship was on a berthing approach to a dock. The Master took the con about 0.5nm from the pier, with the ship making about 7 knots.

When the vessel was about 0.37nm from the pier and making about 6 knots, the Master began the near 180° rotation to port in order to back into the berth and make a starboard docking. Two of three bow thrusters and both azipods were online.

The Master, staff captain, and a pilot were stationed on the port bridge wing. The ship rotated to port, with its stern swinging to starboard toward the pier. It needed to clear the pier’s northernmost mooring dolphin. The staff captain managed communications with the forward and aft mooring decks; he also operated a starboard bridge wing camera (using a joystick), which allowed him to see the pier and mooring dolphins.

The chief officer and another pilot were located on the starboard bridge wing. The first officer was stationed at the forward console to monitor the ECDIS – which used integrated radar – and inform the Master of the vessel’s distance to the pier every tenth of a mile as it approached the terminal. The second officer was stationed at the console at the back of the bridge. A helmsman and a lookout were also on the bridge. A crew member, who was in charge of the aft mooring deck team, was stationed on the stern to provide the vessel’s distance to objects and the pier by radio when requested by the staff captain on the bridge.

After the vessel began rotating, the first officer stopped calling out the vessel’s position relative to the mooring dolphin at the end of the pier. Instead, the Master relied on the bosun’s distance callouts via radio and the ECDIS display on the bridge wing to identify the vessel’s position relative to the pier, using the ECDIS.

The Master also used the starboard bridge wing camera operated by the staff captain to note when the ship, moving athwartships to starboard, was clear of the dolphin, allowing him to go astern to the berth. However, the crew stated that the camera froze during the manoeuvre due to a hardware issue. When the vessel was almost completely turned, the crew member aft reported the vessel was in line with the dolphin.

Soon after, he reported the vessel was 56 metres away from the dolphin. About 30 seconds later, he reported the distance as 35 metres and closing. Very shortly after, the ship’s starboard quarter struck the mooring dolphin at the end of the pier. Vessel damage was minor, but damage to the pier was estimated at $2.1 million.

The investigation found, among other things, that the cruise terminal pier had been extended northward by 120 metres with the addition of two dolphins and a connecting walkway about a year before the accident. However, this change was apparently not communicated to the responsible hydrographic authorities. As a result, the pier was not accurately depicted on any navigational charts.

Therefore, the vessel’s ECDIS showed the original, non-extended pier. Even so, as the vessel approached the pier, the weather was clear, and visibility was good. The Master and bridge team should have been able to see the extended pier and added dolphins. However, none of the members of the bridge team reported the extension as the vessel approached the pier. Instead, the Master relied on the ECDIS – which showed the old, inaccurate Electronic Nautical Chart (ENC) – to determine the vessel’s position relative to the pier.

The investigation determined that the crew member calling out distance aft was giving accurate distances to the pier’s northernmost dolphin from the ship’s stern. However, the Master incorrectly assumed the bosun was calling out how much clearance the ship would have as the stern passed the dolphin.

The crew member had either not been properly briefed before the manoeuvre or had received no instruction as to what exactly he was expected to communicate to the bridge team. Had the Master and crew member clearly understood what distances were being communicated, the Master and bridge team may have been aware of how close the vessel was to the dolphin and could have taken action to avoid the casualty.

- There is no substitute for clear, concise communication. In this instance, notwithstanding good visibility and daylight, the nine person berthing team either miscommunicated or under-communicated, thus paving the way for a negative outcome.

- Although an excellent navigational tool, ENCs can be inaccurate for a wide range of reasons. In this case, we observe that the berth extension of 120m completed about a year earlier was not reported to the hydrographic authority. As such, the ECDIS image the Master was referencing was not a reflection of reality.

- It is good practice in navigation and manoeuvring to use more than one source of position data input.

Source: The Nautical Institute

Do you have info to share with us ? Suggest a correction

About Author

Marine Insight News Network is a premier source for up-to-date, comprehensive, and insightful coverage of the maritime industry. Dedicated to offering the latest news, trends, and analyses in shipping, marine technology, regulations, and global maritime affairs, Marine Insight News Network prides itself on delivering accurate, engaging, and relevant information.

About Author

Marine Insight News Network is a premier source for up-to-date, comprehensive, and insightful coverage of the maritime industry. Dedicated to offering the latest news, trends, and analyses in shipping, marine technology, regulations, and global maritime affairs, Marine Insight News Network prides itself on delivering accurate, engaging, and relevant information.

- Real Life Incidents: Near Miss In Open Water And Good Visibility

- Real Life Incident: Poor Situational Awareness Leads to Collision

- Real Life Incident: Monkey’s Fist Knocks on Office Window

- Real Life Incident: Paint Storage Slip-Up On Ship

- Real Life Incident: Checklist Mentality Is A Burning Problem

- Real Life Incident: Vessel Speed Exacerbates Bank Suction

Latest Case studies Articles You Would Like:

Subscribe To Our Newsletters

By subscribing, you agree to our Privacy Policy and may receive occasional deal communications; you can unsubscribe anytime.