Real Life Incident: Communication Difficulty Leads To Collision

A bulk carrier was down-bound in a river waterway. While the vessel was in a lock, there was a change of pilots. During the exchange, the disembarking pilot mentioned that it was difficult to communicate with the bridge crew because of their lack of proficiency in English.

After the arriving pilot had exchanged information with the Master, the vessel left the lock. The pilot requested the assistance of a police patrol boat from vessel traffic services (VTS) in order to clear any pleasure craft in the area below the lock exit, as many small boats were present for a fireworks show. As they progressed downriver, the Master left the bridge. The bridge team now consisted of the pilot, the officer of the watch (OOW) and the helmsman.

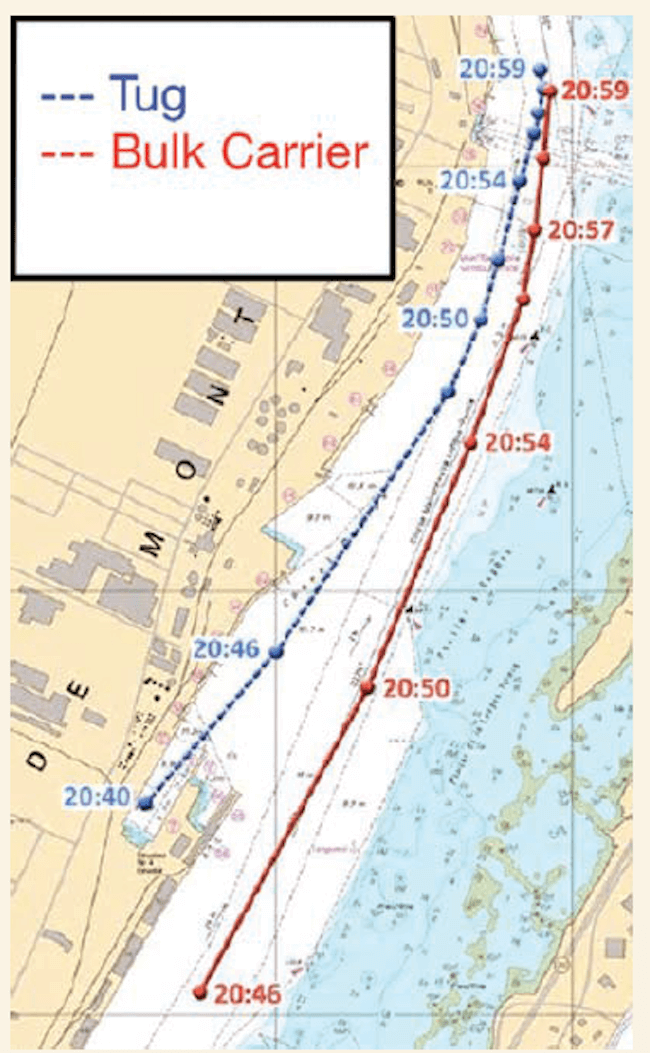

At about the same time, a port tug left its berth down-bound to assist another vessel. VTS granted authorisation for the tug and gave information on up-bound vessel traffic, but did not mention the downbound bulk carrier exiting the lock.

As visibility was good, the tug Master navigated visually and did not turn on the radar. The ECS was not used either. The bulk carrier, now making way at a speed near 12 knots, was upstream and behind the tug at a distance of approximately 0.9nm. The tug was visible to the pilot.

On the bulk carrier the pilot asked the OOW to turn on the forward deck lights to make the vessel more visible to the pleasure craft and to have someone posted forward on the forecastle deck to stand by at the anchors. The OOW appeared not to understand; at any rate the requests were not acted on. The pilot asked for the Master to come to the bridge. When the Master arrived, the pilot again requested that the forward deck lights be turned on. The Master turned on the lights.

The pilot, now on the port side of the bridge, observed three pleasure craft ahead of the bulk carrier moving towards the vessel. Two of them altered course to starboard in order to meet port to port. The third altered its course to port; in doing so, it disappeared from sight behind the bulk carrier’s cranes. The pilot went to the starboard side of the bridge in an attempt to see the third pleasure craft but then lost sight of the tug. Not being able to see the pleasure craft, the pilot altered to port.

When the pleasure craft became visible on the starboard side, the pilot ordered starboard 20° and then hard to starboard. Once the swing of the vessel was stopped, the pilot ordered that the vessel be kept steady at 357°. By this time the tug was less than 100m away on the port side, and the pilot was on the starboard side of the bridge – still without a view of the tug. As the pilot walked back to the port side of the bridge, there was a screeching sound. The pilot now saw the tug on the port bow moving away from the bulk carrier. The Master on the tug had, at the last minute, become aware of the bulk carrier behind him and had engaged both engines in order to move away from the approaching vessel.

Following the collision, the tug’s engineer checked for water ingress. The pilot on the bulk carrier and the Master on the tug spoke over VHF radio and confirmed that they had collided and VTS was informed.

The damage sustained by the tug was sufficient to merit a dry dock and it was out of service for almost seven weeks. The bulk carrier was not damaged, but traces of black rubber from the tug’s fenders were apparent on the hull.

Some of the findings of the official report were:

- The pilot on the bulk carrier was not monitoring the tug at the time of the collision. The bridge crew was not assisting the pilot by maintaining a lookout or using navigational equipment to advise the pilot of relevant traffic.

- The language barrier between the bridge crew and pilot contributed to communication difficulties and led to ineffective BRM at a critical time during the voyage.

- The VTS officer’s high mental workload at a critical time probably caused him to omit the down-bound bulk carrier when reporting traffic to the tug.

The Master on the tug was unaware of the bulk carrier for a variety of reasons:

- VTS had not reported the down-bound vessel.

- The Master was not using all available navigational equipment such as radar.

- No effective lookout had been posted.

Lessons learned

- It bears repeating that all navigational aids should be used not only to help position a vessel but also to give the bridge team the most complete situational awareness possible.

- If there are communication issues within the bridge team that is the time to redouble one’s vigilance.

- Vessel bridge crew and the pilot are a team and need to work together for a safer voyage.

Reference: nautinst.org

Do you have info to share with us ? Suggest a correction

About Author

Marine Insight News Network is a premier source for up-to-date, comprehensive, and insightful coverage of the maritime industry. Dedicated to offering the latest news, trends, and analyses in shipping, marine technology, regulations, and global maritime affairs, Marine Insight News Network prides itself on delivering accurate, engaging, and relevant information.

About Author

Marine Insight News Network is a premier source for up-to-date, comprehensive, and insightful coverage of the maritime industry. Dedicated to offering the latest news, trends, and analyses in shipping, marine technology, regulations, and global maritime affairs, Marine Insight News Network prides itself on delivering accurate, engaging, and relevant information.

- Real Life Incident: Vessel Collision in Good Visibility

- Real Life Incident: Severe Injury To Deck Crew While Leaving Berth

- Real Life Incident: Departure Damage in Very Restricted Waterway

- Real Life Incident: Low Situational Awareness Has High Impact Consequence

- Real Life Incident: Fouled Anchor in a Designated Anchorage

- Real Life Incident: Fire On Barge Carrying Scrap Metal Causes $7 Million Worth Of Damage

Latest Case studies Articles You Would Like:

Subscribe To Our Newsletters

By subscribing, you agree to our Privacy Policy and may receive occasional deal communications; you can unsubscribe anytime.

Web Stories