Real Life Accident: Hydrogen Sulphide (H2S) Gas Almost Kills Crew Members On Ship

A chemical tanker was instructed to load 2000 tonnes of crude sulphate turpentine (CST), a Category X cargo under MARPOL Annex II. The cargo was to be discharged to another tanker via a ship-to-ship (StS) transfer at a receiving terminal. Although there were several experienced crew members on board, none of them had any previous experience of this cargo, or knew about its associated hazards. The ship’s Safety Management System (SMS), Procedures and Arrangements (P&A) Manual, cargo checklists and procedures were all followed, despite there being no information on this specific cargo.

Prior to arrival, a briefing was conducted by the chief officer. The material safety data sheets (MSDS), were not available at the time. Accordingly, the hazards of the cargo (toxicity of hydrogen sulphide (H2S), organo-sulphides and mercaptans) were not properly discussed. On arrival, the shipper handed the vessel a cargo-specific MSDS. The ship’s manager also supplied a generic MSDS which did not mention H2S. Because of the delayed and incomplete information from a large number of sources, the crew remained largely ignorant of the dangers of the cargo. The receiving STS ship, the terminal staff and even the cargo surveyor, who also obtained a generic MSDS from the internet, were also largely unaware of the dangers. Although there was a week’s delay in the transfer operation, information on hazards was not updated among the parties because everyone thought they had the correct data. As a result, the surveyor used a respirator filter that was ineffective against H2S vapours. The accompanying seaman, who opened the tank’s Butterworth hatch (see Figure 1), was not protected. He did not query why the surveyor was wearing a respirator and yet he was not.

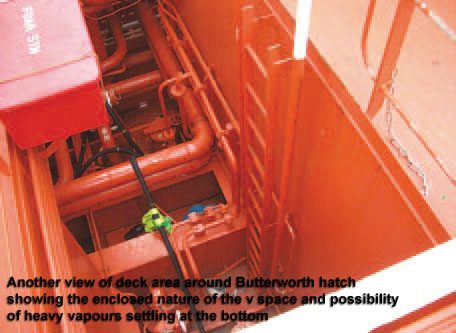

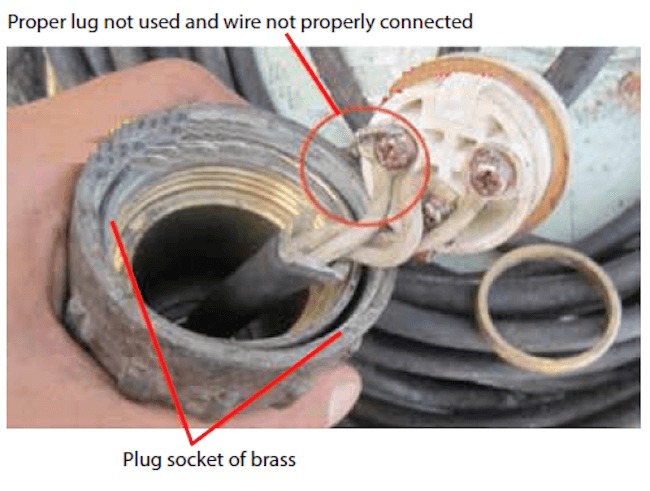

During the transfer, which was completed without incident, there was a very strong odor of rotten eggs, yet no one investigated this properly and no reference was made to the MSDS to verify the cargo hazards. Following the STS transfer, a mandatory pre-wash of the tanks was carried out. As several fixed washing machines were defective, portable machines were lowered down the Butterworth hatches. As the washers agitated the tank’s atmosphere the pungent, heavier-than-air cargo vapors were driven out through the opening and settled in the vicinity of the hatch.

When the pre-wash was completed, a seaman went down to the hatch to remove the portable washer. Although part of the upper deck, the area around the Butterworth hatch was in effect an enclosed space: there were limited openings, unfavorable natural ventilation and the area was not designed for continuous worker occupancy (Figure 2). As he descended the ladder, the seaman became unable to detect the pungent smell, began to shake uncontrollably, and collapsed across the open hatch.

Very soon afterwards, another crew member saw the casualty and alerted the chief officer. The chief officer informed the Master, who went to the bridge to sound the general alarm. Instead of using the terminal’s emergency procedures, he informed the agent of the problem. The agent, in turn, informed the Harbourmaster, who contacted the emergency services. Meanwhile, the chief officer attempted to rescue the seaman, but without testing the atmosphere and without wearing breathing apparatus. The inevitable happened. As he approached the seaman, he lost his motor functions, could not speak, and slipped in and out of consciousness. Another seaman attempted a further rescue from the walkway above the Butterworth hatch. He took large gulps of air before descending to the casualties. He was badly affected by the cargo vapours, but fortunately managed to struggle back to the walkway.

Soon afterwards, crew members wearing breathing apparatus rescued the chief officer and seaman. They were transferred to hospital, where, fortunately, they made a full recovery.

Root cause/contributory factors

- Use of deficient and different versions of MSDSs;

- Complacency, leading to lapses in procedures in this case there were inadequate safety briefings and an acceptance of strong smells;

- Failure to use breathing apparatus despite the strong odor of hydrogen sulphide H2S;

- Defective fixed washing systems;

- Potentially dangerous spaces were not identified – the Butterworth hatch was effectively in an enclosed space;

- Would-be rescuers acted on impulse and emotion rather than knowledge and training – the initial rescue was attempted without breathing apparatus and without testing the atmosphere;

- Terminal emergency procedures were not followed – only the chief officer was briefed on terminal emergency procedures, so the Master was not aware of the correct procedure to expedite assistance.

Reference & Image Credits: nautinst

Do you have info to share with us ? Suggest a correction

- Real Life Incident: Vessel Collision in Good Visibility

- Real Life Incident: Severe Injury To Deck Crew While Leaving Berth

- Real Life Incident: Departure Damage in Very Restricted Waterway

- Real Life Incident: Low Situational Awareness Has High Impact Consequence

- Real Life Incident: Fouled Anchor in a Designated Anchorage

- Real Life Incident: Fire On Barge Carrying Scrap Metal Causes $7 Million Worth Of Damage

Latest Case studies Articles You Would Like:

Subscribe To Our Newsletters

By subscribing, you agree to our Privacy Policy and may receive occasional deal communications; you can unsubscribe anytime.

Excellent Lesson . It’s an eye opener to every one imnvolved in the business of maritime operatins and Safety,Health and Environment

Jayanthi Latchaiah

Safety Engineer

Ruwais Refinery

THANKS

Thanks for sharing, so the other seafarers can learn from this accident. Under root cause/contributory factors I would add that the deck watch and crew involved in operations didn’t have (should have) on them, operational and calibrated personal H2S gas detectors (monitors), when working with cargoes containing H2S. (see ISGOTT sec 2.3.6.4)

Capt. Sablic Ivan